AGNSW’s section of the exhibition had the most artworks that I particularly liked, and I have selected seven artists from the exhibition here – all not only great works of art but with fascinating stories behind them. There were plenty of other discoveries in the rest of the gallery too, including paintings from Australia’s art history, which was educational and mirrored NZ’s art history; the Aboriginal art collection, which I found wondrously diverse (knowing little about it beyond the traditional designs); and some further contemporary artworks.

Scroll up for Parts 1 and 2. Quotes are from the exhibition catalogue or the wall notes, and photos are my own.

Yhonnie Scarce

Death zephyr (2016-17). Hand-blown glass, nylon thread, steel armature.

At first glance, this is an incredibly beautiful work, crystals floating across the gallery in a melifluous cloud. The meaning is much more sombre and sinister. The artist grew up in Australia’s vast militarised test-firing zone, the Woomera Range. This abuts the restricted zone still contaminated by the British nuclear tests at Maralinga in the 1950s and 1960s – as does her maternal grandfather’s Country. The effects of the tests on local indigenous communities has been suppressed, although “Many attribute sickness and death to the radioactive black mist that moved noiselessly across the desert” – quite apart from the forced displacement of those communities. It is fitting that Scarce’s medium is glass, transforming sand through intense heat, just as the bombs crystallised the desert sands. “A momento mori, if you will, to an industrial contempt for human life.” The shapes reference the traditional bush foods of the Aboriginal people: long yams, bush bananas and bush plums – now contaminated for all time.

Taloi Havini

Habitat (2017). Multi-channel digital video.

Another environmental disaster, this time the abandoned Panguna copper mine in the artist’s native Bougainville (an autonomous region of Papua New Guinea). Whole villages were relocated, receiving a pittance in royalties in compensation for their land. Since the mine was closed in 1989 (after a local rebellion), people struggle to make a living from the devastated and toxic environment left behind, growing crops and prospecting for meagre amounts of gold. A combination of aerial and tracking shots across three screens produce a beautiful, ethereal, painterly effect which belies the havoc wreaked on the inhabitants by the Australian company responsible, Conzinc Rio Tinto.

Gunybi Ganambarr

Coastline of Grindall Bay (2016) Milnjurr (2016) Gapu (2017) Details + Buyku (2016)

Sand, natural pigments on bark Galvanised steel Rubber Hollow logs, natural pigments

The artist, from remote northeast Arnhem Land, balances respect for traditional artistic protocols with innovation, often using found materials. Here he is commenting on the changes brought about by local mining and associated building projects. Coastline of Grindall Bay represents an aerial view of the saltwater estate of Garrapara, significant for maintaining clan relationships, including the resolution of disputes. The miny’tji (sacred clan designs) which decorate the works have denoted ownership and responsibility for the land for centuries. Milnjurr and Gapu make use of discarded industrial remnants; Gapu is made from an old conveyor belt used to transport minerals from the Nhulunbuy bauxite mine and alumina refinery away from the area – and hence it becomes a symbol of the dispossession of land and resources. Once again I am struck by the great beauty of the artworks dealing the ugly side of colonisation, industrialisation and corporate greed.

Megan Cope

RE FORMATION Part 3 (Dubbagullee) (2017) Hand cast concrete oyster shells, black sand, copper slag

Yet again a reference to the dispossession and capitalist exploitation of land and resources. The huge Dubbagullee midden was located where the Sydney Opera House now stands; it is one of many middens destroyed by the early settlers (burning the shells for lime for mortar, and building over the area) and thus wiping away connections to the Ancestors and sites of ceremonial significance – as well as the villages and their communities. “Cope thinks of middens as a form of Aboriginal architecture. They are man-made structures that trace a record of occupation and culture over many centuries, debunking the colonial claim that Australia was terra nullius, or unoccupied territory.” Yet the intention of the artist is not simply to describe dispossession, but to reclaim concepts and spaces “autonomous of Western frameworks of being and knowing”.

The work reminds me of some of Ai Weiwei’s artworks (such as Sunflower seeds), which also refer to injustice, exploitation and environmental damage, though in a very different context.

Keg de Souza

Changing courses (2017). Vacuum-locked bags, dehydrated local produce.

De Souza is known for her architectural structures, in which events take place – conversations on relevant topics, with a sharing of knowledge. Changing courses relates to the changes in Sydney’s food culture brought about by colonisation, urbanisation, gentrification and immigration – and the associated displacement of people. It connects “food, place, identity and domestic life”.

Without at first knowing of the more negative meaning, I felt the work to be a wonderful celebration of the diversity of Australian communities and their contribution to the national menu – and perhaps it is also that. It is, too, a reminder of how the creative imagination can assemble everyday objects into a monument of great beauty and interest. But I also had the feeling that this place of shelter – perhaps a metaphor for a home, a city or a country – can in fact be quite flimsy; perhaps it is food, or rather the sharing of food, that can unite and sustain it.

Tom Nicholson

Comparative monument(Shellal) (2014-17) Framed mosaics, boxes, video.

During WW1, Australian soldiers fighting the Ottomans discovered a sixth-century mosaic from a Christian church in Palestine. They dug it up and shipped it back to Australia, where it is now embedded in the wall of the Australian War Memorial. Artist Napier Waller was commissioned to produce a complementary mosaic to reach to dome; he used an alternative art deco colour range. Nicholson’s concept was to propose a new Shellal mosaic using the tiles from the original Waller mosaic, to be shipped to Gaza, as reparation for the original theft. As a symbolic substitute he has therefore made (or rather, two craftsmen from Jericho made) replicas of the original Shellal mosaic using Waller’s colour scheme – with the addition of some Australian flora and fauna. These reconstituted mosaic segments are being boxed up, apparently ready for shipment. Accompanying these is a video with archival footage of the mosaic being dug up, as well as the present location in what is now Israel, and featuring the Bedouin activist Nuri el-Okbi, who makes parallels between the loss of the mosaic and the loss of Palestinian lands.

I found this a fascinating story, conveyed in an imaginative multi-media way. I was also struck by the idea that reparation can be done, if not literally, then by symbolic means, which at least acknowledge the commission of past wrongs.

Helen Johnson

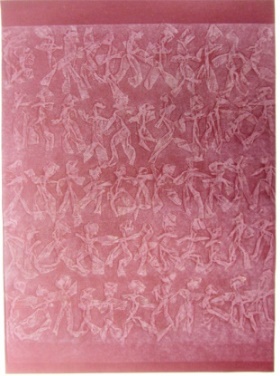

Empire play (2016). Synthetic polymer paint on canvas.

Helen Johnson’s paintings challenge white myths about Australia’s colonial past. They draw on historical and contemporary sources such as prints, political cartoons and films, portraying life-size generic archetypes, both representative of, or agents of, European power and privilege, and other more lowly characters. “More suggestive than didactic, Johnson’s layered compositions deftly play with framing, legibility and perspective to undermine the idea of historical certainty.”

There are no notes to explain the meaning of Empire play, other than the general description of the body of her work (there are three paintings in this exhibition). The background drawing includes an explorer and land surveyor, and someone holding a cup with what seems to be freemason symbol. The four women I assume are transported convicts; the reverse of Johnson’s paintings contain scribbled notes and sketches related to her research for the paintings, and this one includes a judge, and a note “bound for Botany Bay”. Three of the women are on their knees, perhaps pleading not to be sent? Or giving thanks for deliverance from the nightmare journey at the other end? Two Roman centurions watch over them, presumably a reference to imperialist power. In her signature style, the artist has provided the painted figures with the barest of facial features, so that they remain generic: is the meaning here that we of European heritage are all implicated in colonisation, or that these women represent the victims of injustice too?

Johnson uses an interesting painting technique: for example she uses paint-soaked garments to push the paint into the canvas. The paintings are hung loose from the ceiling, like theatre backdrops (and the title of this one is Empire play); this makes the viewer an actor on the stage, rather than a passive bystander.

2

2 3

3 4

4

6

6 7

7